Humans of Aura: My mission to find Dad

Humans of Aura

Mike O’Dwyer: I wasn’t looking for a hero – I was looking for a dad

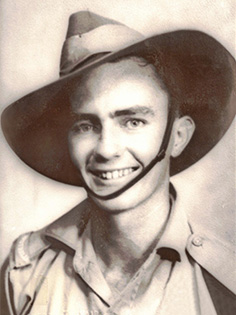

I was only 10 months old when my father died. He had been a teacher at a little town called Muttaburra when he enlisted in the army. Muttaburra is right in the heart of Queensland and when I was young it was extraordinarily remote with only dirt roads and not even radio reached. It was a town that went through periods of prosperity, drought, floods and fire.

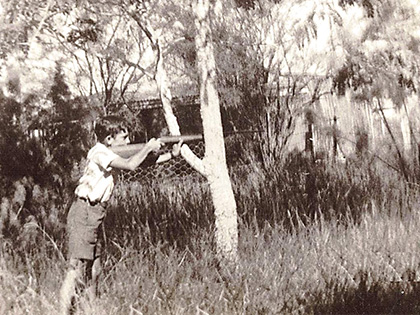

When my father was killed I would say my mother, who had been a loving mum, sort of became unstuck. That meant I was separated from my sister and sent off to various homes, none of whom wanted to know me. I lost count of the schools I attended. But Muttaburra was my base – I was sent away and came back and sent away again. Because of this I was always the “new kid’’, even back in Muttaburra. The new kid isn’t who you wanted to be. That kid was the one always to be sacrificed to the bullies, so I became good at avoiding trouble. I’d go bush around the back of the town – it took me hours to get home from school but this way I’d wear out the posse after me. My grandparents were, in a sense, my parents. Those were the days when you left in the morning saying “I’m going now, Grandma’’ and all she would say was “OK, be back in time for dinner.’’ No one ever worried that at eight I was heading out with a rifle over my shoulder. But the butcher in Muttaburra had closed so I would go out looking for fresh meat. I’d bring home pigeons or I’d go down to the river and get some ducks.

I grew up knowing nothing about my father – I didn’t even know his name. My mother couldn’t speak of him and nor could anyone else in the family. But when I was about 16, I started taking notice and I discovered his name … James Joseph O’Dwyer.

Dad had ‘jumped’ into Borneo from a B-24 heavy bomber on the 30th June 1945 – only six weeks later the Japanese surrendered. He’d spent two and half years in training with the army’s Special Forces and was a commando in the Z Special Unit. His first time at war was on that day when he and three others (including their leader Flight Lt Alan Martin) jumped out of the B-24 flying at 500ft above the jungle canopy.

The aircraft was way off course. Alan Martin landed outside the Japanese-held area, while my father and two others parachuted into the middle of enemy-held jungle headquarters that had somewhere between 500-800 Japanese soldiers. If it weren’t true you wouldn’t believe it but it has been verified by all sorts of people, including the Japanese. My father and a Kiwi landed right on the roof of the main barracks. They were dropped 10km off course, that itself was a distressing outcome for the air crew and jumpers alike. These were guys who were supposed to be getting in with secrecy but they landed in the middle of Japanese headquarters, 20 miles behind enemy lines.

The Japanese had been having their evening meal, it was about 7.30, and they were in a building next to the main building. They had to hand in their weapons apart from their katanas (swords) to have dinner and that’s when our guys landed on the roof with a hell of a noise. The Japanese came out to see what was going with only their swords and our guys were armed with Thompson submachine guns. My father and the other two engaged the Japanese in combat with 20 of them dying before our guys miraculously escaped without injury into the jungle during all the confusion. They had lost contact with their leader and he never saw them again.

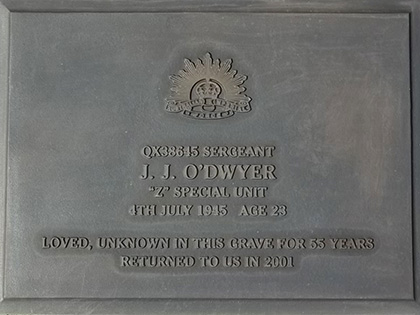

Truckloads of Japanese headed out after my father and the others who managed to survive for three days before they were ambushed, captured, tortured and beheaded on the 4th of July. Then all of a sudden the war was over, everyone was happy, cheering and hopping on boats to go home, and my mother was expecting my father to come home.

Truckloads of Japanese headed out after my father and the others who managed to survive for three days before they were ambushed, captured, tortured and beheaded on the 4th of July. Then all of a sudden the war was over, everyone was happy, cheering and hopping on boats to go home, and my mother was expecting my father to come home.

My mother suffered terribly – her heart was torn apart. She removed every trace of my father’s life and never mentioned him ever to me. The whole family was sworn to secrecy by the Department of Defence so said nothing. There was no one I could speak to – did I even have a father? I grew up in this crazy world thinking fathers were optional that they came from a strange place like the Moon or a warehouse. I actually saved up to find the warehouse to rent a father!

When I was around 16 I asked a relative and this time it was like “yes, you had a father!’’ I had a father! And I got a name. Over the years I got more substantial answers. Then someone said he’d been in the Z Special Unit, it meant nothing to me at the time, and that he had been killed in the war. I asked “so where is he?’’ No one knew. I went from not having a father to having a father, then not knowing where his remains were. I travelled down to the Australian War Memorial spending days and weeks digging stuff up.

I assumed that’s where the story would end, beheaded in the jungle of Borneo all these decades ago and no grave. I went further afield and started to find Japanese reports and after 28 years I found Alan Martin and I phoned him. He was retired living in Western Australia and a recluse. He always blamed himself, as leader, for the loss of the other three – but he didn’t need to blame himself – he was a gentleman and he did everything right. He needed me to tell him I forgave him – I didn’t need to – but he needed to hear it.

Forty years after the war he returned to that same Japanese campsite with me – he put all his ghosts to rest. We went to that little village in the jungle and people who knew things were still there. I tracked down the lady who had found my father’s body in the Semoi River and she came to the site and pointed out on the riverbed where her husband had dug a grave. Where she pointed had eroded and I estimated that now my father’s body was at a 12-foot drop. I hired local subsistence farmers giving them money to dig. We started with four and I paid them $1.50 a day and that’s why we ended up with 65. They were smiling, saying “Wow this is the most money we’ve had in this village since World War II’’ and they were joyous with $1.50. They dug for about five days but my father’s remains weren’t there, they had long since gone.

When the war was over his remains were removed from the river bank – the Japanese were trying to hide a few things and he was reburied, as nicely as they could, in their compound. Then the Australians came in with the War Graves people and interviewed everyone. They found two of the guys but not my father’s remains. The reason was simple, it was the end of the war and they just wanted to go home and get out of this rotten jungle with its rain, mud, malaria. Morale was in the pits, so they didn’t look properly. They removed a body from the compound to Balikpapan to the Australian cemetery and this body was a ‘John Doe’ – that was my father. But at that point he was completely lost to the authorities – they had him and they didn’t realise. Then they removed him from Balikpapan (Indonesia) to Sandakan (Malaysia) and then to Tarakan (Indonesia) and then to Labuan Island (Malaysia). I had to trace it all the way – five times. I knew something had gone on and had to be like a rat up a rope to find out what. The War Graves people at the time did not want to admit to me that they had made such an administrative stuff up to lose my father’s remains then to have those remains moved that many times before we ended up finding him.

I then had to get enough information to prove that it was actually my father’s grave under the marker “Known unto God’’ in Labuan. Now that spot has his name and reads “Loved, unknown in this grave for 55 years, returned to us in 2001.’’ That really is the whole story there.

Mum, who remarried and widowed again, is still around and now 96. Would you believe she sat on the banks of the Semoi River when we were expecting to dig up my father’s bones. How someone could go from pushing all that away for so long to be brave enough to sit on the banks of that river in Borneo, I don’t know. The other person sitting beside her was Alan Martin.

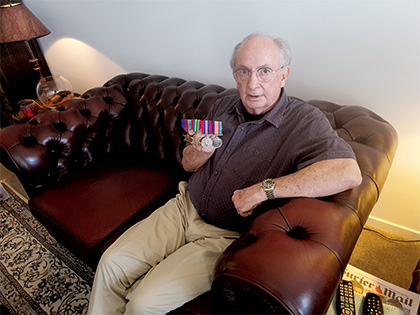

My mother is encouraging me to write the book of my story and hold nothing back. Mum is 110 per cent behind the book that I have delayed writing for a long time.

The story of losing a father, of course, is not unique. These days while I don’t dwell on it, I now know what happened but when birthdays, Christmas and Anzac Day roll round, when the fourth of July comes around, the pain is the same. All that happens is you learn to deal with it a little differently.

The story of losing a father, of course, is not unique. These days while I don’t dwell on it, I now know what happened but when birthdays, Christmas and Anzac Day roll round, when the fourth of July comes around, the pain is the same. All that happens is you learn to deal with it a little differently.

At Aura Holdings we feel very privileged to have so many wonderful residents living in our villages. A very big thank you to Mike O’Dwyer, resident of our Kingsford Terrace Retirement Community at Corinda in Brisbane, for sharing this incredible story with us.