Humans of Aura: Coups and the KGB

Humans of Aura

Bill Newnham: A high-achiever’s life engineered for adventure

I was born in Brisbane in 1945 and my family relocated to Nambour where I did all my schooling. At Nambour State High I was in the Air Force Training Corp and found myself in the rather silly situation of learning to fly before I could learn to drive. I had a good time in school and did pretty well academically. I was offered a range of scholarships, including a flying scholarship, an offer to do medicine – and I seriously thought about that for a while as I wanted to be a neurosurgeon – even one to do acting at NIDA, but I ended up choosing engineering at UQ.

My background is in theorical physics and mechanical engineering and later in project management. I’ve spent about 40 per cent on my adult life working and living overseas and have had some adventures.

After university, I worked for a few years as a consulting engineer in Brisbane before suggesting to a colleague-friend that we should start our own engineering practice. He said ‘yes but why do it here, why not do it in Cyprus?’ I went home and asked my wife how she would feel about living in Cyprus, she agreed and three months later my friend and I hung out our shingle in Cyprus.

My friend was Cypriot by birth and his uncle was the deputy head of the police force in Cyprus so he was able to introduce us to lots of people who were very useful, including the then President Archbishop Makarios, the wily priest. It was in that period after we arrived in early February 1974 that I had a little run in with the KGB.

Henry Kissinger and Andrei Gromyko, the respective foreign ministers of the US and Russia, were meeting in Cyprus so I went out to the airport to see Kissinger arrive, then decided to stroll down to the Russian Embassy to get a look at Gromyko. I walked in wearing a suit and dark glasses just like everyone else. The Greek-Cypriot Presidential Guard and the KGB were both there and after 15 minutes or so I guess one of them asked the other ‘is he one of yours?’ and the reply would have gone like ‘no, we thought he was one of yours’. I was arrested by the Cypriot Presidential Guard and the KGB. I made reference to my friend’s uncle and I was later freed. That was a rather interesting little excursion!

By July 1974 the Greek Colonels – the junta – were in power in Athens and decided they would bring Cyprus back into the fold by staging a coup. About 18 per cent of the population on Cyprus was Turkish and the Turks at the time had one of the biggest standing armies in the world so they invaded. We got up one morning and from our kitchen window on the ninth floor saw a battalion strength of Turks dropping from parachutes. That’s when things heated up. The Greek junta had tried to grab President Makarios but he was evacuated to safety by British special forces. The Turks then overwhelmed the island because of their superior force.

We were evacuated by the Canadians, who were part of the United Nations force in Cyprus, in a Hercules to Cairo and then a couple of days later they airlifted us by helicopter to the Canadian base in the Black Forest area of southern Germany. After that we got on a train to London. I left Cyprus literally with the clothes on my back and my wife had one change of clothes. The only things you grab are passports and any money when the boys with uzis are down in your basement!

In London we got jobs and had to start again. I was working with a large engineering contracting firm and from there had two options to go to Iran as a project director to build 16 hospitals or go to Norway to work for the Mobil oil corporation. Fortunately, I decided to take the Norwegian job as six months later things got a little messy in Iran.

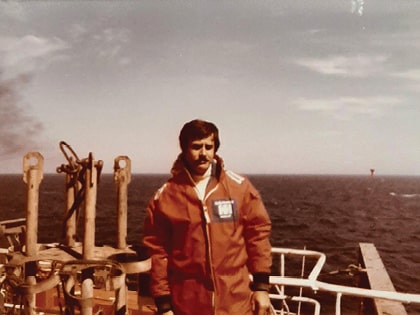

We lived in Stavanger in southwest Norway for nearly 15 years and that’s where our two sons were born. I worked in various roles with Mobil and the last couple of years I transferred to the Norwegian state oil company. It was the second largest oil field in the North Sea, a massive project, much bigger and more complex than the construction of the Channel Tunnel.

Stavanger, about the size of Toowoomba, was a boom oil town where 18-year-old kids drove around in Porsches. When we first arrived, the Norwegians were just starting to feel the effects of oil revenues. The population went from relying on timber and fish canning to becoming extremely wealthy. Norway now has the largest sovereign wealth fund per capita in the world.

Norway gave us a very cushy and cushioned lifestyle where everything was done for you when you worked for a major oil company.

My wife Pamela also had a very successful career – she worked for Mobil before I did – and was at the pointy end of the oil business. She was the head of costs and contracts for the drilling operations with an annual budget of half a billion dollars to spend.

We came home to Brisbane in 1989 with a couple of young lads who were ready to go to school. There wasn’t much around in my speciality on the east coast of Australia in offshore oil and gas so I ended up retraining myself in management consultant and worked here, Singapore and Indonesia in that field for 18 years.

Then I decided I’d had enough of that and transferred to the mining industry having previously only worked in oil and gas. I ended up with a French-Canadian group SNC Lavalin, an engineering and construction group and they shipped me off to Colombia in South America in 2011 for a few years.

I went over as a project director for a coal mine, Cerrejon, that was on the Caribbean coast in northern Colombia – that was good fun. I went on ‘bachelor’ status, working eight weeks then having two off when I’d fly around the world back to Brisbane, then do it all again. Sometimes I’d travel via London to catch up with No.2 son, Tristram.

Colombia was quite a fascinating part of world to live. I had an apartment in Bogota and arrived with a stereotypical expectation of a drug-ridden shoot ’em up city but it was actually far more genteel than Brisbane on a Saturday night. By the time I got there the South Americans had received a lot of support to improve their military and police to get rid of the processing part of drug trade – it went to Mexico. Of course, you still had to be a little street smart but I never saw any street fights or anything like that.

While living alone in Bogoto I had the time to finish a Masters degree and learn some Spanish, although it was never to the standard that I’d learnt Norwegian. When you arrive somewhere and don’t speak the language it is obvious that you are going to be lonely, hungry and thirsty which gave me a high motivation to learn the language.

When the project in Colombia came to an end, I took a few small jobs in project management until I drifted into retirement about 2014-2015. During my working life I dabbled in this and that and gave it my best shot. You can have 20 years of experience repeating the same thing 20 times or you can have 20 years of varied experiences, and I think I have always chosen the latter. When something gets a bit boring, I start looking for something new.

The one career project that stands out to me is the North Sea Statfjord field – the biggest ‘Meccano set’ I ever had – it was massive. We had a cash burn that if converted to today’s Australian dollars would be around $1 billion a month over seven years – it was an $85 billion project. We had three major offshore projects, loading systems and onshore gas terminals so it was highly complex and highly interesting. It really was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me. We had people from all over the world, about 68 different nationalities working on the project. The field has now come to the end of its productive life and I think they are using it as a storage reservoir for CO2 – an interesting extension of the facilities.

I don’t really have a lot of regrets, but I occasionally wonder how life might have been as a neurosurgeon. Or it might have been nice to fly fast jets for a while but that would have got a bit boring after a while. I guess I liked the dirty fingers choice of mechanical engineering.

I am glad that I managed to spend time with our boys. I travelled a lot when they were young in Norway but was always home at weekends when we’d head to the countryside or ski in the winter.

Now Pamela and I reside very happily at Kingsford Terrace Corinda after leaving our home of 21 years at Chelmer with three levels, lots of stairs and four bedrooms. We have been here for a year.

I still have lots of interests and like to stay busy as I’ve found it hard to switch off after such challenging full-time work. I have all the theory in my head as an engineer but I have poor skills on the tools so am enjoy attending Men’s Shed twice a week. There I can get on the tools to learn manual skills such as forging, casting and blacksmithing. Another two days of the week I attend the UQ healthy living gym and am still involved in Toastmasters public speaking.

When things settle down post-Covid we are both keen to travel to the many places we have not visited. And I need to get back to my Spanish, revising those irregular and regular verbs which are hard work and harder if not speaking every day.

At Aura Holdings we feel very privileged to have so many wonderful residents living in our villages. A big thank you to Leslie Buffett, a resident of The Atrium Lutwyche, for sharing experiences from her eventful life.